ME2/3: The Accidental(?) Autobiography of Bioware As An EA Subsidiary

Note: this was originally posted on my offshoot blog theinfernocafe.wordpress.com, back when I thought I was gonna post there but only posted one thing. I wrote this on March 19, 2015, which feels like 100 million years ago now. Now that Blogger is owned by Google and actually has features, I might start using it again. Or maybe not. I guess we'll see.

It seems only fitting that the first official post of the new blog be about Mass Effect 3, as the final post of the old blog was. By now, it's a worn subject, even with me. But while reading a feature by Melissa Loomis on Game Rant about alternate theories on video games that will change your perspective, I got to thinking about my own theory that I dropped casually on my podcast not too long ago in regards to the Mass Effect series. I'm not going to link it, because this article is not about shilling my own content (if you want to find the podcast, you easily can), but suffice to say that trying to restate said opinion on Game Rant kind of blew up from a quick quote into an enormous post. So enormous that it didn't fit, so I figured, why not just get into here?

Personally, I think ME2 and ME3 are rather unsubtle metaphors for Bioware's forceful acquisition by EA and the results of said selling out; ME2 being the hopeful belief that everything is going to work out, and ME3 being the grim realization that what's happened to them is non-reversible and everything they were afraid of being true. Why do I think that? I'm glad I pretended you asked!

Cerberus/The Illusive Man

In Mass Effect 2:

Mass Effect 2 is, at its core, not an adventure game, but a heist story. Only, this heist is not for any material possession, but for the soul of a company that by unfortunate circumstance has gone all in. Shepard, under the renegade eyes of the Illusive Man, is putting together a team to infiltrate an alien slave collective (I wonder what that could represent) and change the fate of the galaxy. Only the best will do, and everyone knows the odds are long. But ultimately it ends on a hopeful note if you put the work in. This is important to understand when discussing the thematic elements in the characters, because they all work back to a central point: Bioware being sold to EA by its parent company is a scary turn of events, but with the right steps, could pay off big.

I think the Illusive Man is the most tragic figure in the series, by way of metaphor. The Illusive Man represents the leadership of Bioware, who thought that they could, through craft, maintain control while using EA's money to produce their titles. In Mass Effect 2, he's driven, intelligent, but most importantly, he's made to appear as morally grey as possible. He's not evil for evil's sake; he has a goal and practicality is his guiding principle, and he achieves that goal through his organization, Cerberus.

Remember, this is not the Cerberus of the first Mass Effect. That group was nothing more than some faceless, aimlessly malignant terrorists written for a series that was fundamentally about something else. This Cerberus, by contrast, is nothing but faces and idealism, starting from the top. This change in perspective as told through the eyes of Shepard and Joker's defection to Cerberus is reflective of Bioware itself. The Illusive Man is everything a person trying to glamorize themselves might come up with when trying to be rebellious. He's clearly well off, with the all the cliché shorthand traits that indicate good taste; he sips his whiskey slowly, smokes his cigarettes dramatically, and always knows just what to say to come across as perceptive, measured, and perpetually a step ahead of everyone else. He's got a darkness, but it's a sexy darkness.

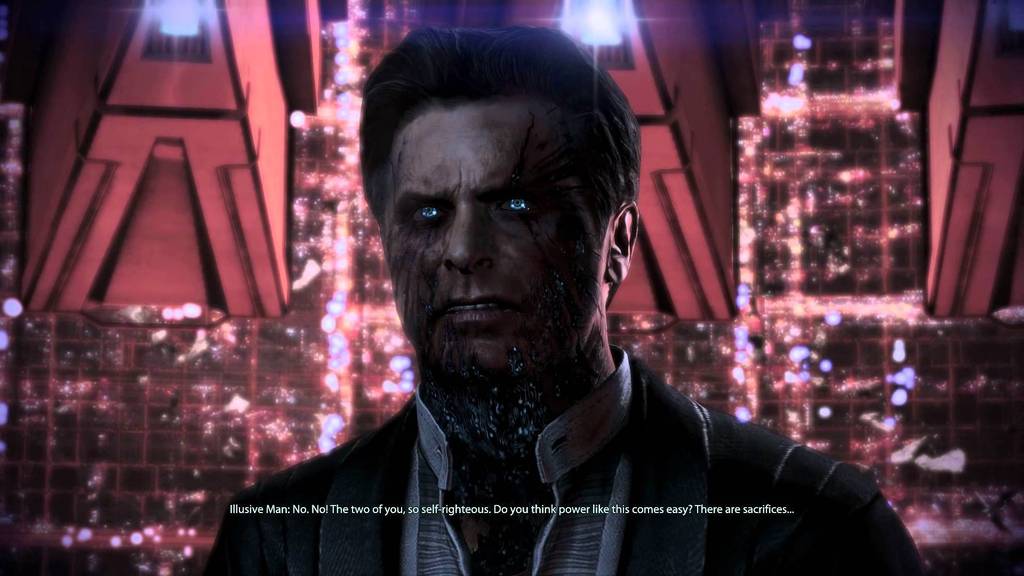

Nothing communicates the essence of the Illusive Man better than his eyes. They're clearly Reaper tech, but reclaimed, bent to his own will. They're the first thing you see when you look at him, and they're the core of what he is: a visionary looking at a future that he alone can command through aptitude and force of will. This is frequently evident in your interactions with him. He always has an answer to pointed questions, always has a justification to all moral quandaries. And he comes across this way because he exists in a game that, at its core, agrees with him.

Speaking of Cerberus, let's talk about Jacob for a second.

I'm not excited about it either.

Jacob exists primarily as your moral assurance that the Illusive Man is on the right path. He's an unequivocal good guy. He's also the first major character you meet after the destruction of the Normandy (more on that later.)

You may remember him for another significant reason though: he first appeared as the protagonist in Mass Effect Galaxy, the mobile-only spinoff game that had you mindlessly shooting your way through dozens of enemies, on a mission to save peace talks with Batarians (by killing said Batarians). It featured a dialogue tree with absolutely no meaningful impact on the game; people would just react slightly differently. The hook of this game (that is, why you would spend money on it at all) was that it would unlock hidden content in Mass Effect 2. Don't take my word for it:

What was that hidden content?

If you guessed, "a single throwaway line of dialogue from a random NPC," either you actually spent money on this game, or you're just as cynical as EA!

The Mass Effect Galaxy version of Jacob is more or less interchangeable with the main character of any modern FPS; he knows english and he shoots everyone. These are his primary defining traits. The Jacob in Mass Effect 2, by contrast, is nice to a fault. He has your back right away, and initially is the only person who is unquestionably on your side.

This feels deliberate. There's no real reason for Jacob to be in this game. They don't do anything exceptionally interesting with his character; he has no particularly compelling arc to deal with. His seat could easily be taken by any of the characters from the original game. Once we consider the nature of creative control, it becomes more clear.

Jacob is a reclaimed character. Prior to Mass Effect Galaxy, Bioware had full creative control over how its characters were depicted. Then comes along a mobile game at a time where mobile games couldn't possibly encapsulate what the Mass Effect series was supposed to be about. Especially one that was clearly put out quickly to make some money ahead of Mass Effect 2's release. Including him in Mass Effect 2 at all is conspicuous; depicting him as basically an entirely different person is a statement. Let's talk about another character from Mass Effect Galaxy who had no business being in Mass Effect 2.

Shots fired!

Miranda Lawson has no business being in Mass Effect 2. Actually, I should clarify. From a storytelling perspective, Miranda Lawson has no place in Mass Effect 2. She is, from beginning to end, an absolute cliche. She's a perfect genius with a perfect body, an ice queen, and eventually, through discovering her long-lost perfect sister, finds her inner humanity. Everyone has seen some permutation of every part of her story a million times.

This is not to say that Miranda is a bad character. But let's be honest: they did a whole hell of a lot more with Garrus, or Tali, or hell, Zaeed, and he's a damn DLC character.

RIP, Sarris

Miranda is also a reclaimed character, but this time, primarily through her arc rather than directly through her personality. Miranda's arc is one of a rich, gifted girl finding her identity and humanity outside of the clutches of her possessive father. But not entirely; she's really only traded the possessive father (EA, or the fears one associates with being possessed by EA) for another (EA as 'manipulated' by Bioware). On top of that, she finds new meaning in reconnecting with her sister, who is really just an alternate reality innocent version of her that, through noble sacrifice, can live happy and free from tyranny.

On its own, I'll grant you that this is a pretty convoluted metaphor for me to insist upon. It's easy to think of this character as just another piece of eye candy (that suddenly appeared after EA took ownership of the series), only showing up to sway your dollars with the power of boners. A cynic would say Miranda was put in this game to give the series major headway in Rule 34 country.

I'm a serious character with real human emotions!

But remember this point, because within the context of how this game pairs with Mass Effect 3, it becomes majorly creepy and depressing.

In Mass Effect 3

In Mass Effect 3, the best way to describe the Illusive Man is "Captain Ahab with a melted robot face." He's precisely none of the things he was depicted as being in Mass Effect 2. This time around, they play off his sudden mega-evil mania as "showing his true face," but the reality is much sadder than that.

If Mass Effect 2 is a hopeful game about an improbable heist, then Mass Effect 3 is about what happened when the Nazis found Bioware's attic. It opens up with everything you know being destroyed. Gone is any hope of changing the galaxy (or by extension, Bioware). This is about scraping out another day until the inevitable. Thematically speaking, Mass Effect 3 treats the hopeful pretense of Mass Effect 2's charming underdog attitude as Icarus' prelude to flight. It could not scream "we were fools to dream, and now our very identity is but fuel for the grinder" more loudly from beginning to end.

Gone is the Cerberus helmed by a mysterious visionary. The Illusive Man is reduced to a desperate, craven lunatic, obsessed with what has clearly become unachievable, and willing to gamble everything he has and is away, no matter how futile the end results will inevitably be. It's fitting that by the end, his face has almost completely melted off, as it fittingly represents the complete dismantling of his vision. His eyes, no longer a symbol of dominance but of subjugation. He's nothing more than a cautionary tale now, and he dies picturing the future he could never achieve. I'm sure this is totally unrelated to the founders of Bioware quitting post-ME3.

Video unrelatedIn ME2, the Illusive Man's power comes primarily from idealistic volunteers, many of whom are the best in their field. In ME3, his power comes primarily from people he's enslaved in one form or another.

Pictured: Consent

The image above is especially important when discussing the finale, but we're not there yet. Suffice to say that for now, the game paints a pretty clear picture not only of what being a reaper slave is like, but also what they look like.

Now let's talk about Jacob and Miranda again.

Jacob, the moral center of Cerberus in Mass Effect 2, is so far removed from the series at this point that he's barely in Mass Effect 3 at all. What else can you do with a good man who fights for what he believes in? I mean besides kill them, of course. Jacob is in Mass Effect 3 for roughly five minutes if you remove all the combat, and it essentially boils down to, "I'm still a good guy, and I think we can win this thing! Anyway, I'll see you never again in this game!"

I'm sure everything will turn out great!Meanwhile, instead of "dismissively short," I would describe Miranda's arc as "mercifully short." She likewise appears in the game for hardly any time at all, but boy do they go deep into uncomfortable metaphor country in that span.

If in ME2, Miranda's relationship with her father was a metaphor for Bioware's fears of a 'relationship' with EA, and her connection to the Illusive Man represented the relationship Bioware could cultivate through craft, then ME3 is where things start to be less Pretty Woman and more Irreversible.

Don't google that reference. Just assume it's as bad as it sounds.

Having left Cerberus in the time between ME2 and ME3, the Illusive Man now wants to kill Miranda for no longer participating in his vision quest. While Shepard helps Miranda dodge assassination attempts and look for her sister (who has been kidnapped by aforementioned psycho father, Henry,) she admits in a quiet moment that she feels guilty for wanting to install a control chip in Shepard's brain when they met. Subtle!

Meanwhile, Henry, who is now an employee of the Illusive Man, has set up a false sanctuary to trap fleeing refugees and experiment on them under the guise of "saving humanity" (again, the hammer-like subtlety of this metaphor is remarkable). He captures Miranda's sister, lamenting when she tries to shoot him that she's been tainted by "Miranda's poisonous influence." It's at this point that, if left to her own devices, Miranda either dies, murders her father, or both. Considering that at the end of ME2, the Illusive Man helped to relocate Miranda's sister, there's a better than 100% chance that he handed her over to Henry just for a chance to kill Miranda.

I really wish it wasn't.

Remember that this is pretty much all they can do with her character. She doesn't have any personality outside of what she brought thematically to Mass Effect 2, so like Jacob, they're playing the only card they can. And that card, in this case, is utterly cynical and dark. In Mass Effect 2, Miranda's father is an ambiguous threat, portrayed (perhaps even rightfully) as the truly wronged party. We don't even see his face, another way of subtly downplaying his existence. We only know what Miranda has told us about him; in this way, Bioware is distancing itself from the reality of EA's negative image. The Illusive Man is the more real character, and they have a clear, strong relationship.

However, in Mass Effect 3, the father is not only in the flesh and evil, but is the Illusive Man's lackey. An extension of his will. It's clear now that what Bioware (or Bioware's leadership, more specifically) initially downplayed is not only true, but said leadership has become complicit in the awfulness. If the Reapers ultimately own the Illusive Man, and the Illusive Man owns Henry Lawson, then this family reunion's undertones are even darker than they first appear. And Henry goes out spewing the same lunatic rhetoric as the newly-evil Illusive Man: we can control Reapers! We can save humanity!

The Council

I think the Council represents Bioware's relationship with whatever EA executives were assigned to handle the developer's output.

In Mass Effect 2

In ME2, the Council is depicted as short-sighted and caring only for the version of reality which makes them most comfortable. If this doesn't sound like corporate executives to you, google, "corporate executives." And this is especially jarring from a more literal perspective because there's really no reason for the Council to disbelieve in the existence of Reapers. Any story arc that has them pretending Reapers aren't real should have been utterly resolved in ME1, when they are nearly killed by one. No group of people outside of a horror film has willfully ignored so much raw data since 9/11 truthers. To be brutally honest, this is probably the only reason we even see the Council at all. Remembering that ME2 is taking the stance of "we can pull a fast one on EA if we try," it's not surprising to see that the Council is shown to be incompetent and utterly disconnected in every way possible.

Aside from the fact that they're literally phoning it in, Bioware makes sure that the Council's refusal to acknowledge the Reapers as a real threat sounds as stupid as possible. This is a group of people who, if you'll recall, interacted directly with one two years prior.

Making a turian do quotey fingers is how you make him look like the dumbest, smugest asshole possible.

They did this tap dance up to practically the credits of the first game, so why are they doing it again, exactly? I used to think that this was a statement on the nature of politics, a swipe at the nature of politicians to be ignorant to problems that don't directly affect them. But this theme has already been explored to death in the first game - the only reason this scene could conceivably be in ME2 at all is either for laughs, or to make a point surreptitiously. Considering the scene is utterly devoid of comedy, I'm forced to conclude the latter.

In Mass Effect 3

Meanwhile, in ME3, they're ineffectual yet again, but now the criticism against them is infinitely more mournful and angry. They become obsessed with saving only their own species, and convening a summit so as to delay acknowledgement of their own culpability in their failures. Keeping in mind that Mass Effect 3 was internally rushed (the EA way), and that Bioware started losing major employees as early as Mass Effect 2, and faster than Jim Jones lost followers at Jonestown, it's hard not to imagine the Council being trotted out as an increasingly less-subtle punching bag.

Again, this is a common trope (the incompetent government fails in a crisis) in this genre, but again again, there is no real reason for the Council to be in this game in this capacity. Everything they say in Mass Effect 3 is so goddamn stupid that it should be interrupted with gunfire.

The Council only exists to talk about more meetings and more voting on meetings is gonna fix everything.

The Council in ME3 is utterly worthless, and only exists for you to hate them, again. They're what should have been an asset, a body of counsel if you will, that through short-sighted stupidity, become yet another obstacle. But I've wasted enough time even bringing up these bit players, like they deserve to share page space with the Illusive Man. These games are principally about three characters, and I'm overdue for the other two.

Commander Shepard

There's a lot of ground to cover with Shepard, so let's get the basics out of the way. The default, intended Shepard is paragon male. Sorry, I didn't (and would never) decide that, the cascade of promotional material did. Female Shepard didn't even get a real default appearance until Mass Effect 3, and even that clearly wasn't given as much TLC as male Shepard. For what it's worth, I think Hale did much better in the role. But Bioware is owned by a corporation, and corporations don't let females be the stars of their games.

In Mass Effect 2

You'll notice that up to this point, I haven't really called much attention to original Mass Effect. This is mostly due to EA having absolutely zero to do with it. Now that we're talking about Shepard though, I will, because as of Mass Effect 2, Shepard is Bioware itself, and the hope that Bioware is still going to make something that outshines corporate oversight.

In the original game, Shepard is just player character. His narrative importance is largely derived from the fact that the player is experiencing the game through him. There's no reason to believe he couldn't be replaced in a sequel, as was done with Dragon Age, as well as with KOTOR 2. Rather, the original Mass Effect was always more interested in the larger universe Shepard inhabits. Though the game features Reapers as the end-all doomsday antagonists, the game seems far more interested in what this universe would do with that, rather than if the universe will survive at all. Like the Fallout series, or Planescape: Torment, or many others that occupy this kind of storytelling through the societies that inhabit these worlds, it's not really about the place, but the people who make the place. Many of the quests in Mass Effect have you going to some far-flung planet, driving across a series of massive, barren expanses, and engaging in what ultimately amounted to small-scale storytelling.

In my opinion, Mass Effect sets a good framework for this kind of world building. It imprints a firm image of what these imaginary alien species are called, how they interact with one another, and what you can expect from them. I personally have a lot of trouble getting into fantasy games, as many fall into the trap of assuming I'll care about forty different races of elves without any real kind of distinct interactions. Mass Effect does an excellent job of distinguishing its fantasy races. I wanted to learn more about each species. I read the codex. There was clearly a lot of TLC poured into the universe, and the first game really set the stage for more grand space adventures.

Unfortunately, on October 11, 2007, VG Holding Corp, the parent company of Bioware, was bought by EA for $860 million dollars, and the Mass Effect series went from another thoughtful if flawed Bioware game, to the art equivalent of the Alamo.

Let's talk about the opening of Mass Effect 2. The first thing that happens to Shepard is he dies - this symbolizes the old Bioware of yore being no more. How does Shepard die? The Normandy is erased, and he is strangled to death by the vacuum of space. Insert sad piano music.

We hardly knew ye

The very next thing to happen to Shepard? He's rebuilt, against his will, using Reaper technology. This symbolizes EA's money becoming inseparably fused with the spirit of the company. Being his true self will, over time, conceal the hideous scars he's incurred. Or he can succumb to negativity, and, well...

This visual aesthetic look familiar?

Despite these setbacks and his forced "defection" to Cerberus, Shepard is given a bloated, ugly version of the original Normandy, and with it, musters a crew for the heist of the century. Shepard's tone remains defiant throughout: you will not beat us, humanity doesn't quit. We will do what we have to do to survive. This is Bioware's artistic voice. It's not going to be trampled by a soulless corporation. All of Mass Effect 2, from stem to unnecessary DLC, Arrival, is about reinforcing and trumpeting this theme.

In terms of scope, Mass Effect 2 has precisely none of the vision that Mass Effect did. From the way your ship interacted with the galaxy, to the way you left and reentered the ship at port, all of it was smaller, more removed, abstracted from the larger picture, which no longer existed. Mass Effect 2 isn't about telling small stories; it's about how all stories are really about beating the Reapers. There are no planets to explore, no open spaces. Every environment is a shooting gallery, designed to funnel you forward. You never enter a place that could conceivably exist. That's not what this game is about, anymore. It's about defiance.

In Mass Effect 3

Mass Effect 3 is principally about despair, and nowhere is that more obvious than in its protagonist. Shepard spends the majority of the game wading through helpless refugees and friend and former foe alike who've lost just about all hope. When he doesn't trudge off another battlefield, or balefully retreat from another loss, he has nightmares of his failures.

Pictured: Subtlety

The message is clear: chances are, no one's going to win this one. And Shepard, who has been a symbol of hope and change, of possibility and triumph, now dreams unskippable, unending sequences of failures he couldn't have possibly prevented. The only child ever depicted onscreen in the entire series is brutally murdered in the first 20 minutes of the game. That child isn't just Shepard's failure; he's also Shepard's (and by extension) Bioware's naive belief that maybe things would work out. Really, he's the idealism of Shepard boiled down to its purest state, and then Megatron takes a giant Transformers shit all over it. There's a reason he looks like a child version of default Shepard.

The Star Child

So now we come to the Catalyst.

Obviously, the Catalyst represents the horrifying reality of corporate EA. The Catalyst's logic and explanation of how the Reapers work is not unlike how EA itself works: a civilization (or company) becomes big and famous enough, and the Reapers 'acquire' it, transforming it into a new Reaper, a defiled shadow of its former self. If any Reapers die, it is irrelevant, as the Reapers are nothing but tools to an end; a way not of managing cycles (as the Catalyst claims) but of managing supremacy.

And no amount of talking to the Catalyst will convince it otherwise, because he and Shepard are essentially speaking different languages to each other. Shepard speaks the language of art, and the Catalyst speaks the language of corporate greed. This is also why his arguments are circular and easily refuted. Corporations don't need to use actual logic or sense. They make a decision, garble out a justification, and proceed with what they wanted to do in the first place.

The only time they hear alternate viewpoints is when it directly threatens their money - that's why when Bioware initially refused to create a new ending to its game, eventually EA decided "nope, you're making new endings," because EA has never cared for artistic vision, maligned or not, it only cares about the bottom line. This is also why the Catalyst is depicted as a child - because his logic is infantile and small-minded. He's just saying words he heard someone else use, like all children.

By the way, what does the Catalyst say of the Illusive Man? He says that he could never control the Reapers, because they already controlled him. What does that mean? Exactly what it sounds like. You sold your soul to us, and thus, will never own us or subvert us to your means.

The Endings, And What They Mean

Now the endings come into play, and I think the endings dictate the state of Bioware's possible futures.

Firstly, there's Destroy: cast aside all that we have given you and rebuild from nothing. This means the liquidation of Bioware as an entity by means of employees quitting, possibly to reform later as a new company. This is the only option that cuts EA completely out of the picture. Notably, this is also the only ending where Shepard survives.

Wu-Tang clan was....nothing....to fuck with....

Next is Control, which in actuality is submit to control. Become another soulless satellite brand of the mega-corporation. You will survive, but you will watch everything you love go away, until we strip you for parts and toss the rest of you into the screaming void. This is the most realistic option, and was recently embraced by Maxis.

The last choice is presented as the most sinister when taken in this metaphorical context: 'symbiosis.' I've talked before about how this is as close to Hitler's idea of science as you can get, but in the context of this metaphor, I think Synthesis cynically represents Bioware pouring all of their passion and creative vision into corporate success. Shepard is disintegrated into nothingness, and his essence binds the entire galaxy into being one living entity. He bravely erases diversity by empowering EA (through success) to own and control everything. A little seed of Shepard inside all beings in the galaxy.

Can you paint with all the color of the wiiiiiiiiiiiind

In the epilogue, we see the Normandy trying to outrun the consequences, regardless of the choice, and in the end, likewise regardless of the choice, it fails. I think this represents admittance (if not acceptance) by the Bioware staff that no matter the outcome, they are forever changed, and the isolation represents just how far from what once was they now are. If you notice, the world they land on looks a bit like Virmire, which now seems like a moral quandary from another universe.

Later, in a clearly far-flung future, the ancestors speak of Shepard not as a man but as a concept so long-dead that he's become myth. The world they live in now is utterly alien to the one he fought for, and they have no intrinsic understanding of who he was or what he represented.

And then EA cynically tries to hock you some DLC.

Comments